How Is The FLAC Thinking about Intersectionality?

This text, synthesized by the Transformative Learning Working Group (TLWG), condenses the FLAC’s collective reflections on intersectionality, the advantages of using an intersectional framework to develop the next stages of the FLAC, and the ways this framework might translate into how, who, and what the FLAC will decide to fund. We outline a working definition and a series of outstanding questions as tools to guide the FLAC’s thinking moving forward. While this text deliberately centers on intersectionality as a framework that could be adopted by the FLAC, we acknowledge that other frameworks should be explored with the same attention.

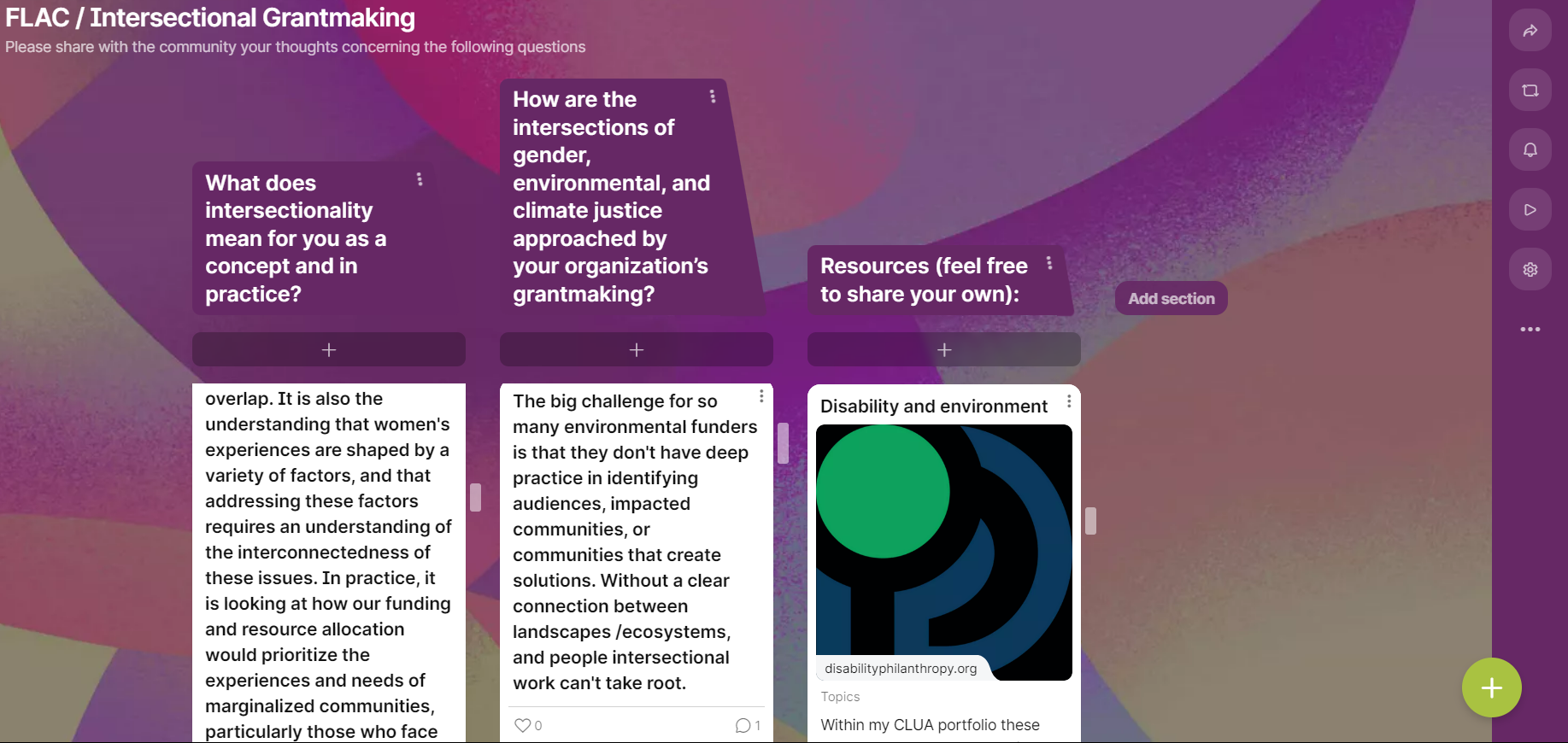

In the Padlet reflections on intersectionality, in the conversations in our working groups, and during the FLAC’s February thematic call, we pushed our thinking about intersectionality as critical social theory and challenged ourselves to articulate how it translates into philanthropic practices. To accompany us in this conversation, we invited Rabiatou Ahmadou from the International Indigenous Women’s Forum (FIMI) and Rana Zincir Celal, a consultant with the Robert Bosch Stiftung’s Support Program on Reducing Inequalities through Intersectional Practice, which convened a diverse group of partners to explore intersectionality.

The FLAC approaches intersectionality as a framework for understanding the causes and impacts of structural inequalities, as a way of grappling with the differences in power between groups, and as a lens that foregrounds knowledge accrued through lived experiences. The framework of intersectionality invites us to embrace diversity and power differentials, holding the complementarities and contradictions inherent in working collaboratively across North–South, class, gender, and racial divides. An intersectional analysis pushes us to acknowledge the origins of structural inequalities while also working to change existing structures of power. As such, the FLAC recognizes that philanthropy is a privileged, oftentimes inaccessible space that has a long and sordid history rooted in white supremacy and colonialism. How we make space for differences in individual lived experiences, while finding ways to work and act collectively to create change, is part of the challenge that the FLAC faces as we integrate intersectionality into the frameworks that shape our grantmaking and governance.

Like any lens, intersectionality has limits to its scope. Some of us questioned its academic origins in the US legal context and consequential relevance to Global Majority movement spaces. We shared experiences about how the application of intersectionality in practice sometimes prioritizes individual differences rather than fostering collective identities and highlighting interdependencies. Overall, though, there was consensus that intersectionality is a generative and evocative framework that helps foreground differences and challenges status quo power dynamics.

Translating intersectionality into institutional mechanisms and grantmaking practices

“… [K]nowledge is power, and giving Indigenous people the know-how to understand how things work at the international level is crucial.”

Challenging the dominant politics of knowledge production, and questioning what has traditionally counted as evidence in funding, emerged as a critical aspect of creating intersectional processes within philanthropy. The importance and need for both creating spaces to learn collectively, and allowing for processes that recognize and render visible different kinds of expert and experiential knowledge, is apparent. Both Rabiatou and Rana mentioned the importance of learning with and learning from a diversity of stakeholders. With FIMI’s focus on producing research for and by Indigenous women and the Robert Bosch Stiftung’s extended exploration of intersectionality with a diverse array of grantee partners, we should consider how the FLAC can engage in producing or supporting the production of different kinds of learnings around effective strategies that target inequality in climate and conservation spaces.

“One thing we came to appreciate in how we designed the support program was the range of competencies and processes needed for an intersectional approach, such as the building blocks of cross-movement solidarity, inclusive processes or language justice. It requires resources, time, and people with the know-how to set these systems up. It takes real commitment from funders to understand why this is important. For groups confronting inequalities of power on a day-to-day basis, having an infrastructure of care, well-being, and protection is key.”

There is also an evident need for new and adapted institutional mechanisms and processes for transversalizing intersectionality. We heard about the needs for shifts in finance and human resources policies and practices. Creating internal protocols that accommodate differences is difficult but necessary.

“We often had conversations with HR or the Finance Department, and we had to explain to them why this or that was important, and they’d understand; it’s so important to have everyone on board. Now, some of the other programs (climate, peace, etc.) are also talking about decolonizing practices, for example, and how we, from our position as foundation employees that are very close to partners, can push our organizations to change internally at all levels.”

Inspired by these conversations on intersectionality, the TLWG workshopped more questions that will help structure both the learning agenda and FLAC’s way forward this next year. Some of these questions include:

What if we fund what we do not know and what we want to learn collaboratively with historically marginalized frontline stakeholders? We could start by framing open questions about what we want to learn about/with.

What are the existing gaps in knowledge and resources for the current feminist climate justice ecosystem, and what is the FLAC’s role in filling those gaps?

What grantmaking model can the FLAC design that is based on continuous learning, experimentation, and diversity of expertise and experience?

What are the legal and compliance limitations of the FLAC’s funding mechanism and its effects on grantmaking?

Who would the grantmaking be directed to (activists, grassroots organizations, women’s funds, networks, coalitions, etc), and at what stages of their formation (new, emerging, unregistered, established)?

What type of funding would the FLAC commit to (long-term general operating, accompaniment, or project/moment-driven support)? What would be the ideal average grant size, term, regional, or thematic parameters? Who should be involved in this decision and how might the decision be made?

What would it look like for the FLAC to fund convenings and opportunities for knowledge co-creation, research, and narrative change across regions and themes?

Will the FLAC prioritize funding initiatives that look at interlocking political, social, environmental, and economic systems even if they aren’t labeled as “feminist” or “climate justice” focused?